An old road called Maryland Route links Baltimore and Annapolis. This eight-mile-long road is also known as the Generals Highway. This road was traveled on by George Washington in his day, from New York to Annapolis, which was the temporary capital of the US in 1783 to 1784. Close by the Chesapeake Bay was a major port that was active in the 17th and 18th centuries. There, slaves were shipped from Africa and subsequently traded. It prompted the rise of plantations along Generals Highway, where the slaves that were brought to work on tobacco products for the European market. Scientists have scoured the area to study how Africans lived in Maryland during those years and they’ve stumbled upon a tobacco pipe that belonged to a certain enslaved women who lived about 2 centuries ago. This find led to many clues about the way of life back then.

Pipes from that era are commonly found in these archaeological areas. This particular relic was found inside a lodging for slaves at Belvoir, a notable house located in Crownsville, Maryland, that was owned by Francis Scott Key’s grandmother. The slaves were quartered 500 feet down the hill where the stately house stands proudly. Scientists were searching for an antiquated campsite by the

An old road called Maryland Route links Baltimore and Annapolis. This eight-mile-long road is also known as the Generals Highway. This road was traveled on by George Washington in his day, from New York to Annapolis, which was the temporary capital of the US in 1783 to 1784.

Close by the Chesapeake Bay was a major port that was active in the 17th and 18th centuries. There, slaves were shipped from Africa and subsequently traded. It prompted the rise of plantations along Generals Highway, where the slaves that were brought to work on tobacco products for the European market.

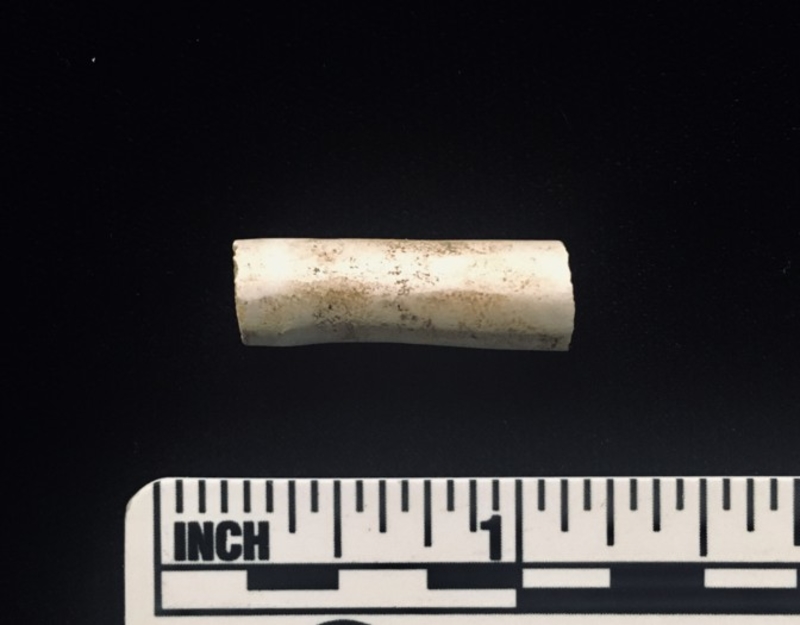

Scientists have scoured the area to study how Africans lived in Maryland during those years and they’ve stumbled upon a tobacco pipe that belonged to a certain enslaved women who lived about 2 centuries ago. This find led to many clues about the way of life back then. Pipes from that era are commonly found in these archaeological areas. This particular relic was found inside a lodging for slaves at Belvoir, a notable house located in Crownsville, Maryland, that was owned by Francis Scott Key’s grandmother.

The slaves were quartered 500 feet down the hill where the stately house stands proudly. Scientists were searching for an antiquated campsite by the French commander Rochambeau, during the revolution, when they found this concrete foundation. In 2014, the historical site was unearthed by a group formed by the Maryland Department of Transportation. During operations, the team’s head archaeologist, Julie Schablitsky glanced up a pipe stem that jutted out of the floor and, along with other finds, traced its age to about 150 to 200 years old. They tested it for DNA and discovered that it was actually owned by a woman and that it matched the DNA of those of the Mende people from Sierra Leone.

They believe the pipe must have belonged to the cook who lived in the Belvoir slave quarter, which had a spacious kitchen and fireplace. Men and women enjoyed smoking tobacco in that period and it follows that the pipe must have been held in the smoker’s mouth, Schablitsky says. “The pipes would have been exposed to body fluids such as saliva and even blood, [and] the porous nature of low-fired clay would have facilitated absorption of fluid, thereby trapping DNA,” she added.

When the ports were still operational, ships used to sail from London Company containing the enslaved Africans transported from Sierra Leone. This establishes the link between Maryland and the West African nation, divided by 4,500 miles of water. Scientists note that their discovery of the pipe owner’s history is somewhat expected, but it’s pivotal evidence nevertheless. The use of DNA makes them trace back ancestry and appoint it to specific archeological sites. If they want to determine if a certain place was inhabited by European or African descent, they now have the technology. If archaeologists begin to test personal artifacts that contain human DNA, we may be able to answer specific questions about ancestry across not only Maryland but the region and beyond.” Schablitsky said.

This project will help scientists in determining the genetic differences between the enslaved people in Maryland (Chesapeake) and contiguous areas. It will also give them a better picture of how the transatlantic slave trade grew, and how specific American communities in the 17th and 18th century were influenced by African culture.

The group of archeologists led by Schablitsky coordinated with known descendants of the people who used to live on the historical property. Wanda Watts is one of them, although her ancestors weren’t from Sierra Leone. When asked to comment about the project, she said, “We have our third great-grandmother’s manumission papers, which are freedom papers. We have all the history of her and her children on the land. We found that all the men in our family were free, their wives were all slaves, and they had to buy their freedom.”

Working with people who are historically tied to the artifacts, properties, as descendants increase the effect of this type of research for communities in Maryland. People like Wanda Watts emphasize the fact that archaeology isn’t just for historical information, “… but to pause and reflect upon the lives of these ancestors who persevered, despite enslavement.” Schablitsky said.